Julia Brennan: Have you listened to Taylor Swift’s Folklore? I am curious to hear your thoughts.

Rick Moody:

I have only just scratched the surface, so my answer is not comprehensive. The first part of my very preliminary reaction is: 1) I really hate The National. I have always found The National truly mediocre, like America’s answer to Coldplay. They are like the Hootie and the Blowfish of contemporary “rock” music. I was given their first album by a guy who is closely associated with them back in, uh, 1999 or something, and I disliked it then, and I have disliked every album since (even if I occasionally like Matt Berninger’s lyrics). So, 2) the fact that Folklore is produced by one of the National masterminds is not, in my view, such as to recommend it. 3) It still has tons of audio massage on the vocals. Maybe even some auto-tuning. This, in my view, suggests that it can’t coexist with a “more organic” sound, which is its selling point. Even if *some of it* was recorded at home, it still sounds like a Hollywood soundproof booth, the purpose of which is to shear off anything that sounds human. Such an approach is the opposite of “more organic,” and though you can, reasonably, make an argument about “organic,” about whether such a thing exists, the solution to the conundrum is not massive audio artifice along with, well, some acoustic piano, to indicate that you are more human than you have seemed in the past. 4) Above all, I think the album is a sort of professional imitation of Fetch the Bolt Cutters, which is not only the best pop record of the year, but, excepting maybe the new Dylan album, the best pop record of the last several years. The reasons why Fetch the Bolt Cutters is so good are numerous. It was recorded at home, it has tons of group percussion playing, it is sort of fucked up and poorly assembled in some ways, the lyrics are outrageously good, she is one of the greatest singers in contemporary music, and this is especially the case now that her range has grown a tiny bit less robust at its edges. There’s something desperately beautiful about Fetch the Bolt Cutters, like Fiona Apple is a person who is unable to avoid telling the truth, and as in all great art the deep truths are contradictory, impressionistic, from the distant past, and so on. If you watch Fiona Apple over the course of her career, she has done just what great artists do, gotten more individual, more unpredictable, more uncompromising, more singular, more strange. It’s all deeply admirable.

It seems natural to me that other artists, artists of any variety, would hear the Fiona Apple record and want to explore, amplify, the gestures of that album. Of course, having said this, Taylor Swift or surrogates will insist that of course all these songs were written before Fetch the Bolt Cutters or TS has never heard Fetch the Bolt Cutters or National guy has never heard her, either, and really he thought he was exploring themes he used on the Frightened Rabbit album he produced, or the Mumford and Sons album he produced, or he thought he was imitating Dusty In Memphis or something. Of course. In a way, all “sophisticated” recordings of the present moment sound like Folklore, the mix of acoustic and laptop-based effects is the sound of the moment. Is it organic? It is the very opposite of organic, really, and if you want to hear “organic,” try listening to Homegrown, the recently unearthed Neil Young album, or Rough and Rowdy Ways, which, one can assume, was largely recorded live. Just because Folklore has an acoustic piano on it does not mean — etc., etc.

That said, well, yes, it is the best thing ever recorded by Taylor Swift. When I hear (THE GUARDIAN, e.g.) saying, wow, we sure hope she goes back to writing pop songs after this worthy experiment, I must pronounce myself surprised. Because the difference between this and, for example, Lover, which I thought was hectoring and vapid, and Reputation, which had no discernible melody writing of any kind, is very significant. I think “The Last American Dynasty,” for example, though it does leave itself open to a critique of Swift’s own significant class blindness, and “Mad Woman,” are both relatively ambitious lyrics, both attempts to broaden the range of lyrical interests—which has more frequently been of the boys-I-have-known variety. I guess, at this point, “Cardigan” is the hit, and I actually think there are many interesting things happening in “Cardigan,” from a lyrical perspective. The way “When you are young they think you know nothing” line is reused and repurposed over the course of the song is definitely genuinely more powerful than, e.g., the rap break on “Shake It Off.” There is narrative happening, there is an interesting use of time, which, you know, is the secret weapon of narrative activity. I surely appreciate aiming higher. It’s funny, it crossed my mind to think about songs that I wrote when I was thirty or thirty-one years old, because I was writing songs then, and I had no grip on how to tell a story in song, nor about how to use the progress of themes across verses. I wasn’t smart, about human beings, at all. Whether it’s the having to grow up in public, or having to produce songs in such ridiculous amounts, year after year, Swift has grown enormously (or maybe we have simply grown alongside her and can see more plainly talent that was there all along, in terms of songcraft).

In all honesty, this is never going to be a songwriter that I want to listen to a lot. And I think there is now, and probably will always be, an aspect of Swift’s career that is about attempting to persuade people that she’s not entirely manufactured, a synthetically assembled machine of contemporary song. Is she not ever donning some garb of authenticity so as to make herself, from a marketing angle, more accessible to an audience and less manufactured? And who is that audience now? It’s not twelve year old girls anymore, and it’s not going to be women in their twenties much longer, and that’s when you have to start thinking about what songs are for and what music is for when adults listen.

PS I have this idea, because your inquiry (and my response), which has got me really thinking about the Swift album, that I should make a piece entitled “In Which I Talk to My Former Students About the Taylor Swift Album,” including our exchange and maybe a couple of other students who are good on such things. Any interest?

Julia Brennan: Definitely interested. Still working on my reply to your first email!

Linzie Lee: I have listened to the new Taylor Swift album. I would love to participate in your piece. I received the blessing of my friend, Julie, who is a Taylor Swift fanatic, to participate. I hope you are prepared for the onslaught of her army. And yes I promise to respond to emails faster.

Rick Moody: If you hate the album, too, that is fine, and appropriate, but I still want to try to understand. That is my goal.

LL: May I just ask— will I be cited by name in your piece? And is this a piece you are planning to place in a publication?

RM: Yes and yes, but probably just publication in a backwater somewhere where only 17 people will read it. If you want to use a pseudonym for the piece I will understand! No problem at all! Can you discuss an early awareness of Taylor Swift, and whether you liked her in your early life, and can you give particular instances? Is there a duty to like Taylor Swift owing to her ubiquity in your youth? I am very interested in specific examples, and specific autobiographical moments of Swift awareness.

LL: First time I learned about Taylor Swift was through Disney Channel because they were promoting “Teardrops On My Guitar.” I think that was her first single. The ingredients of a classic Taylor Swift song were already there. We all know Drew and the forlorn yearning.

Then, I listened to her through these lyric videos on YouTube with bad font and transition slides, and every comment had some iteration of “It’s like Taylor Swift stole my diary.” I didn’t listen to her with other people. I wasn’t a vocal fan, but I think I listened to her almost every day when I was younger.

I don’t have a duty to like Taylor Swift.

RM: Can you speak in a little more detail to a particular song from your youth and its relevance to your youth? When you think back on that time does a Taylor Swift song have a mnemonic capability? Does it help to create and recreate memories?

LL: Truthfully, I’ve been trying to type out an adequate answer for a while now. I was going to bring up “Enchanted” which was my favorite song by her. It makes me think of high school hallways but that’s because I think that she captures adolescent yearning well.

Rick, I apologize but I don’t think I’m the right person for this interview. I’m trying my best to answer your thoughtful questions, but I realize that I don’t think Taylor Swift figured in my life enough to provide interesting answers and contribute to your conversation. All I can think is how successful she is and how artistically uninteresting she is to me. I even relistened to the new album in preparation for this conversation and I was bored and felt nothing.

I apologize.

*

RM: Do you have any wisdom, or feeling about Taylor Swift? I am conducting correspondence with various people on the subject, maybe for a piece on the subject. Can you speak at any length on this subject? Like about some of the songs on Folklore?

Preston Sachs: Here it is:

“The 1”:

Her stuff is always about relationships. This shit is corny. ‘You be the one . . . Meet a woman on the Internet and take her home . . . greatest loves of our time are over now . . . roaring 20s . . .’ is she chastising society for the lack of depth in romance? I feel that such problems of the past still exist now—in fact I think we’ve made more progress in this day and age than previously.

It’s a simple riff. Good on her, she knows her base loves her voice and her style so I’m sure someone jammed out to this.

“Cardigan”:

This is too white for me, man. This is the type of music I hear at Barnes and Noble. I’m sorry but this song made me think of my white friends back in Ohio. I didn’t listen as in depth because it more had an ‘evocative’ vibe/experience to it. Also I need to Google her? Is she still in her 20s?? I don’t like this type of music, but I can see myself listening if I were reading or studying. It’s just so formulaic, like I don’t think there are any risks being taken with this song or the lyrics or the conversation as you might witness in others . . . (e.g. “WAP,” by Cardi B or Megan the Stallion’s “Savage”) . . . It’s so plain and formulaic. There is nothing memorable from this, my brother.

“The Last Great American Dynasty”:

Again, it was sunny… saltbox house on the coast . . . the town . . . it’s so suburban white. This is meant for white women. I can’t relate to any of this, and I don’t want to. Her songs have a conservative like straight edge feel to them. She appears to be empowering women but I don’t know what to think about how she presents the roles of ‘boys’ and ‘women’. If I didn’t know who she was I might have thought this is Christian alternative rock. Rick, I honestly just don’t know where she’s coming from. I feel like this is supposed to be feel-good at the end of the day?

“Exile”:

This is soooo cliche. I know someone who is this cliché and unoriginal and I feel now like they copy and paste this stuff in real life conversation. ‘Seen this film before and I didn’t like the ending.’ I mean there is always conflict in her material and emotions being expressed but the nature or the ‘legitimacy’/exploring this beyond mere dissatisfaction with a relationship seems to be lacking . . . I feel like this was a melody played over a soap opera relationship argument. What I hate is how it romanticizes broken relationships by simplifying them. This is adult Disney.

“My tears Ricochet”:

This seems to be the most layered one . . . Likely because it involves mortality. It’s definitely her most insightful endeavor that I’ve listened to thus far in this album. There’s a genuine exploration of the emotions associated with the loss she describes here and the chord progression (I don’t know shit about music) accentuates the effort. I think that the rumination of the conflict that the ‘significant other’ feels during the loss of their counterpart was very realistic and aptly romanticized in what I thought was her most genuine endeavor yet. There was still a formula involved, but it was a bit more ‘provocative.’ It’s very formulaic, bland, and ‘safe’. It’s not my vibe, but it can serve as respite for many people in this country—after all, that’s why she has the following she does!

*

Rick Moody: Are you ready to begin? Ground rules: you are allowed to ask me questions, too, and you may answer at any length that feels organic, and I will do the same. What is your evaluation of Swift’s new album, Folklore?

Abram Scharf: I listened to tracks one through five about a week after it came out, and then forgot about it until you emailed me. So it’s forgettable, at least.

I’ve got a couple of semi-discrete ideas about T.S. and Folklore, but if the question is how I liked it, or how I would compare it to her previous work, then I’d say that it’s better than her last two records, but much less interesting or fun than anything she did before those.

In short, it’s corny. It doesn’t hold up to rigorous examination along axes of originality, virtuosity, variety, allure/intrigue, unpredictability, or even sincerity (talking about Red here), but despite all of this, I still find it enjoyable to listen to. I wouldn’t tell you that it’s good because it reminds me of my youth, and my sister’s youth, and girls I knew in grade school, even though it does all of those things. I would say that if you found the center of the center, the least interesting person in the world, they would see themself fully reflected in that record, and a lot of Taylor Swift’s music. And that a part of me is that person. Which is humbling.

RM: Can you give me a particular song from Red, and give particular mnemonic interactions, therewith? (I have to say, here, in the spirit of total honesty, that my disregard for Red is complete.) PS, your gloss on “good” is excellent and powerful.

AS: Sure. The album came out during my freshman year of high school. I talked about it with a girl at a football game, and then a couple days later she posted the lyrics “chose the rose garden over Madison Square” on my Facebook page. We started dating the next semester; the song is called “The Lucky One.”

RM: I find the spot-quote-as-interpersonal-marker thing very odd, but I think it’s because I did it a lot of it myself in my middle teens, and then went fleeing in the opposite direction. Now it’s hard for me to remember. Does this memory indicate that the song has merit for you? Does it add to its merit? Or is the memory value neutral?

AS: The turn of phrase is ever so slightly more complex than the similes that Swift usually falls back on, and it’s nice that we were able to recognize that, but the memory doesn’t have much bearing on my evaluation of the song now. What’s funny, though, is that the football game and spot-quote thing is exactly the kind of dorky, adolescent anecdote that I would look for in an early Taylor Swift track (perhaps even the earliest). If I were to make a case for her oeuvre, I would say that she tapped into a very basic kind of millennial nostalgia, writing these kinds of “Landslide” type songs about missing a youth wasn’t even really over yet, at least for the people listening to them.

Also, I think her Folklore persona is supposed to be more reflective than nostalgic. She questions the decisions that she made in her twenties, and tries to figure out how those moments shaped her instead of just mining them for their sentimental value. Still, she could have tried a whole lot harder.

Was there anything you liked, or that surprised you?

RM: I am really interested in whether the current gesture should be understood as artistic ambition or persona maintenance, and in particular I am interested in whether it’s ever possible with Swift that there is NO persona maintenance. Obviously, I am suspicious of her, as an artist. But I also take seriously the idea that she is not 22, now, and she can’t go on with an audience of teenagers.

I want to urge attendance to the stripped down version of “Cardigan,” which is called the “cabin in candlelight” version. And I want to discuss whether it is organic, or a simulation of the organic.

When I was young I used to say: if it feels like there are credibility issues there ARE credibility issues. But now I am suspicious of intuition, which I suspect can be as much of a social construction as anything else, like, say, political belief, or religious certainty. I believe and disbelieve in intuition at the same time. I always feel like there are credibility issues, with Swift, but I have also been just enough in the public eye myself to know how confusing it is to have motives attributed to oneself that are precisely the opposite of the motives intended. The “cabin in candlelight” vocal goes further in turning off the auto-tune, and all the processing on her voice. Does that make it better? What would constitute “good” on Folklore? Reflective?

The other thing is, as I said to another correspondent, is this whole organic thing not, in some way related to what works so well on Fetch the Bolt Cutters, but does not entirely work here?

AS: I don’t buy the reflective stuff, but “Cardigan” is the worst of it, in my opinion. The few lines that place the song in the perspective of someone who’s supposed to be older/wiser become mostly irrelevant by the end, when she opts to validate her imagined younger self, saying that she actually did know what she was doing. There›s no real reconsideration.

Everything about the “cabin by candlelight” version fits too nicely into the whole cottagecore thing, which is itself a corporate trend, as well as a tired shorthand for lone artists doing whatever lone artists do when they’re alone. Fiona Apple took eight years between The Idler Wheel and Fetch the Bolt Cutters, and the latter succeeds because she allowed herself to work slowly, on her own terms, outside of the neverending album cycle that governs the professional lives of most artists. You have to give it time, I think, or else the persona will become this weird, proscriptive thing, writing its own press.

To this point, even the bad songs can now be said to serve some role in the greater narrative arc of Swift’s project, so any organic bits are bound to end up either buried or contradicted. “Good” on Folklore would be an actual commentary on what it means to have a persona, and the toll that it has taken her to maintain it—something that “Mirrorball” does, to a degree.

RM: Now you’re talking.

What would you think of “Cardigan” if it were written by someone not named Taylor Swift? Or, let’s say, by a totally unknown singer-songwriter doing a cottagecore thing because s/he/they actually lives in a cottage? Would it change the song?

Next I’m going to ask you about “Mad Woman.”

AS: I imagine I’d find it confusing for the same reasons that it confuses me as a Taylor Swift song. Is it trying to be sexy? Wistful? Wistfully sexy? That “sensual politics” line, for example, is so weird and unsensual, it makes the stock romance imagery seem insincere, at best. As for the cottagecore angle, who knows. I don’t think it aligns much with the song in the first place, so the question of whether this person actually lives/writes/records in a cottage doesn’t seem too important.

RM: I’m sure I’m going to be alone in making the comparison, but why is “Cardigan” not to be understood as heavily influenced by Weezer’s “Undone—The Sweater Song?” Or for that matter, why should it not be seen as an allusion to the sartorial styling much admired by deceased punk icon Kurt Cobain? If I’m right that the “cottagecore” simulation and presence of a Dessner at the top of the credits is a bid for artistic credibility, then why should we not think that she knows her indie rock? To reiterate, the problem for Swift is audience. If you look at an example like Madonna, which is not an entirely accurate comparison, but still, Madonna’s last truly brilliant album was Ray of Light from 1999, produced when, roughly speaking, Madonna was forty. At a certain moment in the pop music world, unless you mature your audience alongside you, you age out. This is arguably a greater problem in a bubblegum or top forty context, because the audience is that much younger. Swift has to plot a route toward some more reliable audience in the next ten years, give or take, or watch her enormous clout diminish. No doubt these ageist issues in the popular song are even worse if you’re a woman—look at how Linda Ronstadt was treated when she tried to opt out. Note the absence of a Grace Slick on the platform that can still be so successfully exploited by Bob Dylan—see how hard Christie Hynde has had to work just to stay the same. The dynamics are even worse in Black music or R&B. Aretha Franklin’s last high impact crossover pop song was “Who’s Zoomin’ Who,” when she was 43. And she was perhaps the greatest and most original singer in popular music history. In hip hop you’re mostly done by forty, in K-pop probably even younger.

So Taylor Swift has ten years, according to current projections, to find an audience outside of her current home, with which to mature. She could easily make a “country” album again, and I bet she will at some point, though I imagine given her political tiptoeing recently—into Democratic ranks—that may not seem like a truly comfortable fit. She wants to be taken as a “serious songwriter,” in the way, perhaps, that Neil Diamond always did. But with the added feminist angle: she wants to be taken as a serious songwriter like Carole King, or Carly Simon, or Janis Ian, or to take a fine contemporary example Erykah Badu, and that’s the struggle in this album.

I actually think “leaving like a father” in “Cardigan” is really good, and reminds me of Westerberg’s “you might be a father, but you sure ain’t a dad.” A lot of this album seems to be about a bad affair with a much older person gone wrong (maybe the older songwriter she wants to be is Alanis), but what do you think about “Mad Woman,” which, you know, kinda has some literary references.

Here’s an addendum: I was driving children around this morning for a couple of hours, and I had a revelation (a false revelation, but still) that “Cardigan” is definitely about Kurt Cobain. It would be a really interesting development if true. Because then, instead of the song being an autobiographical “confessional” lyric (when we know, really, that those confessions are heavily scripted) it is actually a fantasy, in which the narrator, a songwriter, is metaphorically ravished by a God of Song, then you really have something going on. “Leaving like a father,” then is an indication of how songwriting lineage is like the Electra Complex. There are many ways to tease this idea, that Swift is invoking Cobain at the beginning of Folklore sort of the way Dante encounters Virgil at the beginning of the Inferno, at the mouth of hell. Swift requires Cobain to take her into the underworld of song, to which we will get in subsequent missives. The question is what the word “folklore” means in this context. Does she mean “folk” to be taken literally as a sign of the folk idiom (the album has almost nothing folky about it), or that it is the music of the people, as opposed to, say, Red or 1989, which was the music of . . . girls. There was a dumb advertisement in the late eighties (around when TS was born, let’s say), actually the mid-eighties, and it was for Miller Beer, the worst of domestic beers, I would say as a person who was actively alcoholic at the time, and in this advertisement, for some reason, was the Boston band, the Del Fuegos (one of them is now Dan Zanes, the guy who does quite sophisticated children’s music, and the other was Warren Zanes, who wrote the Tom Petty biography), and there is a voice over and Dan, I think, says, something like “We think of rock and roll as folk music, because it’s music for folks.” I’m constructing this all from memory, but the advertisement is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U5MMct8efwE. I can’t bear to watch. But maybe TS is using “folklore” in this way: as a gambit for the other half of the audience, and thus the presence of a Dessner, and also Bon Iver guy. Anyway, that was my interpretation in the car, “Cardigan” is all about Cobain.

AS: Re: “Madwoman” and literary references, the influence of The Crucible is clear, and generally well-handled, though I’m primarily interested in the chorus, and the more post-war, suburban flavors, like “do you see my face in your neighbor’s lawn?” or “good wives always know.” Am I correct in assuming that you’re thinking of Plath, or, more specifically, “Mad Girl’s Love Song”? Because that’s definitely the lane that Swift wants to be in, I think, and one that could be a good fit for her, once she stops making music videos with magic pianos. My biggest issue with the record–taken here to mean all the songs, bonus tracks, remixes, videos, photographs, and, as of yesterday, chaptered “Selections from . . .” albums that orbit this thing called Folklore — is how she’s still betting hard on the TikTok crowd, and giving them exactly what they want, more often than not. The Taylor Swift Extended Universe, so carefully plotted up to this point, will eventually need to rest on the back of a record that is just a record, and not a breadcrumb trail of (self-)references and creative bona fides.

I thought about bringing up Carly Simon earlier, especially with that “cannons all firing at your yacht” line, but Alanis Morrisette seems less obvious, and more resonant with Plath’s jagged melancholy. Staying in that realm, why not talk Courtney Love and Hole, formed in the ever-relevant year of 1989? I think you’re right on about the titular cardigan, but it irks me that we as listeners have to go back to something so glaringly superficial as her (and Kurt’s) fashionable anti-fashion, something that I now can’t think about without also remembering the six figure sum that it got at auction, and the fact that it was last worn onstage by a mannequin at a Hard Rock hotel.

RM: Okay, you have to clarify, unpack, the TikTok comment for me, because as an elderly person I know about TikTok only two things, 1) that it is a trojan horse for Chinese hegemony, or so a certain political figure says, and 2) that it is a medium where people my age imitate people who are good dancers, occasionally, and then these “parents” lose all dignity. I gather it involves music after a fashion, but I don’t really know how. My kids showed the whole to me for five minutes, but it did not seem to speak to my life experiences.

Check this out. I will be expanding on it soon: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Madwoman_in_the_Attic.

AS: Dancing and data-mining are integral to the thing, though it’s so much more than that, and I, as a non-user, can’t really speak to the multitudes which it contains. Suffice it to say that you only get fifteen seconds per video, with a maximum of four videos playable back to back, so viewers are only ever hearing a fraction of the song in question. That fraction of the song gets used over and over again, and a visual language develops around it, or gets grafted on from another song or soundbyte.

With this in mind, I mostly meant that on TikTok, a song is not a song, but a cataloguing device meant to reinforce dominant aesthetic and commercial trends. Presenting her music as #cottagecore, by, say, rereleasing certain songs as “Folklore: the escapism chapter,” can only be read as her pushing those tracks which have viral potential, and hoping that people take the bait.

RM: Ah, I get it. A sort of hashtag culture spreading out. I feel like the hashtag is the ultimate triumph of Aristotle–things are of note only for their ability to be catalogued and curated, and for no other reason. I curl up and die any time anyone says such and such a hashtag is trending on Twitter (which I ignore), because I don’t care what anything is when rendered as a word or two, but only how this thing, or this sequence of things, this dynamic of things, feels. I assume, to some extent, that this is a post-hoc marketing gesture by Team Swift, but you never know. You never know to what degree people actually want to be integrated into this world of reductive taxonomies. More on “Mad Woman” tomorrow.

AS: Some grist for the mill: T.S. still doing a Target exclusive (likely contractual), but sending signed copies to record stores.

RM: I did hear this. I guess it’s a fine gesture, like her sticking it to Spotify. One has to enjoy any effort to stick it to Spotify.

“Mad Woman” has a few good lines in it, like: “You’ll poke that bear till he claws come out/And you find something to wrap your noose around.” And also: “The master of spin has a couple of side flings,” etc. I suppose our tendency is to want to treat this lyric as an autobiographical lyric, and to want to treat it hermeneutically as though one might figure out exactly which record company exec or publicist guy is being referred to. “Illicit Affairs,” another song on the album seems to cover similar material, but in a more despairing and less angry way. They both, certainly, have a sort of Morisette-ish incision to them, probably “Mad Woman” more than the other. People seem to be treating them as merely confessional. To me, they are less confessional and more about consistency with an idea of femininity in the popular song, especially with certain “auteur” singer-songwriters. The originality, if there is some, is in the severity of the rendering of the feminine subject.

And that’s why I wanted to introduce into the conversation Gilbert and Gubar’s Madwoman In the Attic, which alludes to Jane Eyre in the title, but is more concerned with rendering the feminine characterization, and the role of the woman writer in the 19th century beyond simply the Brontes. What if Swift is less about confessing about her private life, and more about having a nuanced conversation about whether or not women can sing about this stuff in a way that is genuine? The problem with “Mad Woman,” if it’s about her life, is that the character gives away all of her agency to the married “record exec” character and retains no ability to have power in the relationship (except insofar as she gets to write a song about it). It’s psychologically rich, if strange, that one of the most culturally powerful women in popular music has no power in a relationship with some record company exec, etc. Unless her relationship is with Elon Musk (who seems taken) or similar, it’s hard to imagine a relationship in which she is not a complete player, although, of course, anything is possible. The human animal is strange. But as a departure from, and an elaboration on, how women are rendered in song, as related to how they were rendered in literature, “Mad Woman” is sort of genius. If she’s making it all up, that is, it’s kind of genius.

By the way, if you want to hear a really grim and true song on a similar subject try “Private Life” by Pretenders. That’s a song I really love. The use of reggae, so rarely brought off well by white musicians, somehow works here, is really loving, and the sentiment/anti-sentiment of the song is fierce, but unperturbed at the same time. There was a time when Chrissie Hynde was one of the greatest narrators of romantic complication ever, like try out “Birds of Paradise,” if you haven’t heard it. It makes me cry every time. “One time when we took off our clothes/you were crying/they say nothing lasts forever/ we were happy together.” Now that’s a love song. Why so good? Because everyone is implicated, everyone is sad, everyone longs, everyone takes responsibility. Of course, the Pretenders are also powerful because everyone in the band passed into the beyond about when that song was recorded, and so the aura of regret everywhere, in everything.

Or, you know, what about “Buckets of Rain?” That’s a guy’s point of view, yes, but has anyone ever said it so well? Or what about Jolie Holland’s “Mexican Blue?”

I will note that this morning there is also the news about Jerry Falwell, Jr., and his wife, Trump bundler, Becki Falwell, had an affair with a twenty year old, and now he’s coming out with it. Somehow the third-wheel quality of the story bears some resemblance to “Mad Woman,” and in this context it’s hard not to identify with poor Giancarlo Granda. Definitely check out the text messages that Granda gave to the press.

AS: I agree with everything you’re saying about “Mad Woman,” except not about “Mad Woman.” To my mind, “The Last Great American Dynasty” does the same work but with greater humor and nuance, as Swift seems to genuinely identify with Rebekah Harkness, and sees herself in the ways that she was represented by her high-society neighbors (i.e. your record execs or pop stars) and the press. By parroting her (Harkness’s) detractors, Swift places us outside of the relationship, and so manages to ironize the gold-digger/mad woman archetype while maintaining some mystery vis. the subject’s private life. See lines like “The doctor had told him to settle down/It must have been her fault that his heart gave out,” which have a kind of sweetness about them, in that glib, Austenian parlor-speak way.

And I hope Granda writes an album about it. Perhaps he already has.

RM: All the news, the incredibly grim news, has crowded out the Taylor Swift indie rock juggernaut. On Sunday, the Trump auto processional came through Edgewood, Cranston, RI, blowing their horns and advertising their guns. Fun times.

Somehow this reminds me of the period in which people tried to smoke Swift out on her political beliefs, and she tried not to be clear (owing to her remaining foothold in a country, one supposes). Nowadays she is more open, at least she is very open about LGBTQ+ stuff, and she seems to have said a few mild things about the frustrations of the present. It does seem, however, that it’s hard to keep her accomplishments in the forefront of cultural perceptions, right now. I agree about “The Last Great American Dynasty,” by the way, that it is frankly more novelistic in its set of concerns. It does seem to imagine some provenance of her house in Newport. It’s kind of incredible, in a way, that she is advertising her big house in Newport, in this way. Here’s the article from House Beautiful, with photos: www.housebeautiful.com/design-inspiration/a33417436/taylor-swift-holiday-house-folklore-last-great-american-dynasty/.

I think it’s fair to say that the house, and the song about the house, while admirably continuing the “mad woman” theme from the earlier song, are not like unto the indie rock thing. Talking about your big house, however truthful, is an odd choice, unless you’re the kind who thinks real-estate display is admirably American. And it does sort of pull back the curtain on the studied aspect of the album, its generic marketing.

I guess I want to sort of talk about the sound to you. What do you think about the sound?

AS: It doesn’t bother me so much, though I do think that Aaron Dessner’s compositions suffer when he forgoes live percussion. On his records with The National, Bryan Devendorf’s drumming breaks up the more claustrophobic productions, and gives them direction, which Folklore seems to lack, especially near the end. If you check the album credits, you’ll find that almost all of the tracks with live drums were produced by Jack Antonoff, whose record on Taylor Swift songs is spotty, but whose choices on Folklore are less showy than Dessner’s, and play to Swift’s strengths (once again, see “Mirrorball”).

The main pitfall of the faux-glitchy electro-acoustic thing for Swift is that she, like many contemporary pop singers, will end up taking it and doing this sprechgesang thing that approximates the most basic elements of rap, but is delivered in such a way as to not trip that wire. “Seven,” for example, is passable until she goes “Sweet tea in the summer / Cross your heart, won’t tell no other” and then, even worse, “Your braids like a pattern / love you to the moon and to Saturn,” with the rhythm and inflection of a jump-rope or clapping rhyme. I get that it’s supposed to sound kind of juvenile (later: “Pack your dolls and a sweater / We’ll move to India forever”) but it hits my ear so wrong, I can’t let it go.

Maybe part of it is that Dessner’s default mode as of late is dreary and inorganic, something that I found to work well on The National’s High Violet, Trouble Will Find Me, and Sleep Well Beast, but which first got so tall, dark, and looming on Boxer. There you can hear the band getting away from the big guitar sound that they’d been working on with albums one through three, and implementing the synths/preprogrammed elements that they favor now. You see it on “Mistaken for Strangers,” which might be a bit brat-packy, but coheres, and even rips, in my opinion.

Since we started this conversation, I’ve been thinking about the phrase “Another uninnocent, elegant fall / into the unmagnificent lives of adults” from that song, and wondering if Swift didn’t choose Dessner just for his “sophisticated songwriting,” but his single minded commitment to stony, adult aesthetics. At the very least, it was a spectacular choice press-wise.

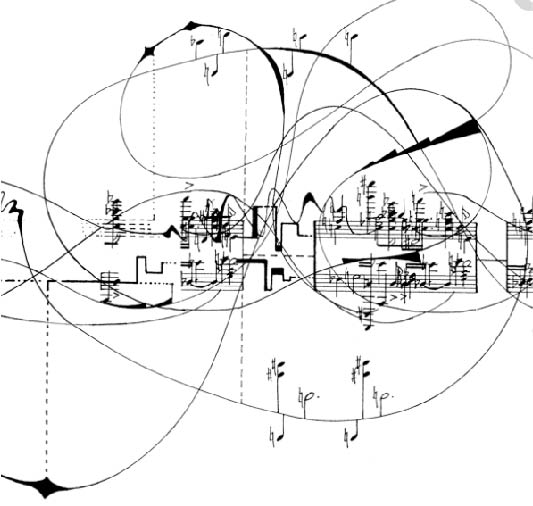

RM: Detail from a John Cage score, herewith. More soon.

RM: Did you see this? pitchfork.com/news/watch-taylor-swifts-debut-performance-of-betty-at-the-acms/

I have to speak to my intense dislike of this song, in the context of the other songs. If I’m right that the purpose of the new album is to try to build bridges with people who care about adult music, viz., adults, the only thing this song has to recommend it is it’s first-person-gender-not-my-own trope, which we don’t even know about till the bridge. Clever, in that creative writing exercise way. Only problem is that in every other way it’s light and insubstantial, and especially in this version, in this attempt to curry favor with the country audience by playing the acoustic guitar live (I am always, I should say, fascinated by her guitar-playing capabilities–the more primitive the better I like it), and by having a harmonica on there, by some poor bastard standing off in the wings. Why can’t the harmonica player be onstage? It’s sort of an Elvis gesture, which is to say a Vegas gesture, not allowing the harmonica player onto the stage.

Just for the sake of exploiting potential differences of opinion I aspire to write about my dislike of

the National, but it seems time consuming. I do, however, love Clogs, the side project of Bryce, which seems mothballed now. It involved actually playing the instruments and not using so many computers. www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSX88PgjtLs

AS: Another thing about “Betty,” which I wouldn’t mention except for the circumstances of the above performance, is the queerbaiting element that here hooks the conservative faction, only to let them breathe easy with the, ahem, gender reveal. Though the album’s been out for almost two months now, and any confusion re: Taylor Swift’s public sexual orientation has surely been Googled away by those who may have found themselves in doubt, her bringing the almost-gay-sounding song into the Grand Ole Opry feels like a classically non-transgressive transgression, to say nothing of the fact that there wasn’t anyone else in the room to cut away to, save for the Harmonica Schmuck.

Does this mean that we’re not going to talk about the John Cage score?

RM: Yes, let’s talk about the Cage score, for sure.

And I totally agree about the faux-LGBTQ thing, which is unfortunate, disappointing, calculating. But even the “kissed a girl” meme, which might have been, which is only verses one and two, is tired and borrowed from LGBTQ+ persons who risk a lot more, and always have. If you follow the Katy Perry “Kissed a Girl” controversy, you may remember that it was preceded (perhaps borrowed from, though without paying up) by the transitionally-immense “Kissed a Girl,” by Jill Sobule: www.youtube.com/watch?v=LUi11Cz4ZUg. Jill didn’t have the dilettante-ish qualities that Katy had and has, and wasn’t tweaking conservative Christians, but living her life, and if you assume that Swift’s aping is aping a gesture that was itself aping, at a certain point, you have to acknowledge that the signifier is part of unlimited semiosis and no longer has a relationship to an original denotative gesture. It’s just part of a code, or advanced capitalism. Jill Sobule meant something. One might also speak of the Madonna-kisses-Britney gesture, as similarly vague, and non-controversial, or even pre-digested for a male gaze. I did think it was good when Flea kissed Dave Navarro on Guitar magazine though. That was a passage through and beyond, even though it would perhaps not be considered that revolutionary in this day.

The Cage score is for a preferred or imaginary version of the Taylor Swift album.

AS: Preferred how? When I think about Cage, I think about stochastic processes, indeterminacy, the I Ching—methods and perspectives that represent the opposite of how contemporary pop hits are thought of and engineered. To that point, Folklore is certainly an attempt to distance Swift from the idea of “the formula,” and I can see how picking Dessner might be seen as just a bid for a more complex formula instead of an attempt at realizing more personal/organic/idiosyncratic modes of expression.

I’ve never read or heard her talk about putting constraints on her own practice, but perhaps that’s what needs to happen, if she’s to progress artistically. Like, no similes. Roll a die, and that’s how many chords you can use. Tune your piano to the value of your water bill, in Hz. With some intermediate calculations, maybe. Who knows what the plumbing situation is like in “Holiday House.”

P.S. I got a host gig at this restaurant that’s set to open in Chapel Hill next month. Kind of fancy. I’ve been going in for training every night with the rest of the FOH staff, which thus far has meant sitting at the tables and taking notes on things like “The Steps of Service” and “Hospitality as Dialogue.” Feels like a grad seminar for waiters. SERV2200. Also— and I just saw this, as I was typing— have you ever noticed how similar the words “writer” and “waiter” are? Spooky.

RM: Vis a vis Swift and the stochastic, which are two things not frequently conjoined together into one spot, I should probably admit that at one point I did embark on a project in which I made a list of every word that had occurred in a Taylor Swift song up to 1989. I would, according to this plan, then make a new song, or at least a discovered poem, a stochastic, freely-arrived at poem, out of the Taylor Swift words, by reordering them. I did not get very far, because, well, my deeply-felt process-poetry mood has found less creative time since I arrived at Brown.

But I will attach a short excerpt here. It will be obvious that this project was heavily influenced by Anne Carson’s translations of Sappho:

1899

1.

{ }

{ }

garden of the

perfectly watched

{ }

actually . . . { }

bleachers

{ }

{ }

charming

{ }

glow hold

{ }

{ }

horse

isn’t

known

{ }

{ }

{ }

night jeans

2.

{ }

bulletproof daydream

{ }

every fix is

{ }

magic

3.

mascara

opened

{ }

passport

red

she

screams thorns

till

snow means

{ }

heartbreakers

{ }

goodbye:

flash castle

4.

breathless boy cages

of December:

{ }

{ }

I’m a glow hospital

I’m an insane lock monster

I’m a permanent sidewalk

I’m a sky necklace

I’m nothing’s kiss

I’m heaven in green

I’m your dance classroom

I’m a torture weekend

I’m a wonderland of scars

I’m scarlet problems

I’m a phone mistake

I’m Miss Laughing Hindsight

I’m fragile and gone

I’m a crystal bullet

I’m your forever ghost

{ }

RM: That was it, anyhow. So maybe it is possible to conjoin John Cage and Taylor Swift into one project. PS, that was really funny about “writer” and “waiter.” I remember, in my unemployed period in 1983, really spending a lot of time thinking about the words “no experience necessary.”

AS: I love that the word “bleachers” features so prominently. She only uses it twice, I think, with one in each pre-chorus of “You Belong With Me,” first rhyming with “T-shirts,” then “sneakers.” It’s also the reason that we’re even talking about Swift right now, as a kind of bookend to your original criticism of Red, which was inflammatory, but hardly as much as the kinds of “bleachers” that you compared it to. I’m listening to it presently, Red. It’s the last CD of hers that I bought, or plan to buy.

I just had to skip “I Knew You Were Trouble.,” in part because it’s ridiculous, but mostly because the next track is “All Too Well,” which is the closest she gets to earning that Joni Mitchell comparison she was angling so hard for. And now I turned the CD player off, because the song after it is “22,” which I can’t listen to without feeling like my brain is itching. So I understand where you were coming from.

As stated before, my interest and allegiance lies with the early Swift, who gave us “She’s Cheer Captain and I’m on the bleachers,” and then donned a brown wig to play that Cheer Captain in a music video intercut with scenes of her singing her own music into a hairbrush. It’s juvenile in the best way, which is to say, sincerely juvenile. She knew what made a Taylor Swift song great, and I think she could very well find that again at some point, as an older, more thoughtful writer, musician, and performer. It would have to be something new, and honest in a way that could be very disarming, coming from an artist whom myself and many of my friends actually learned how to be jaded over. I look forward to it, the music forged in the Swifty of my soul.